This is one of two posts I’m making for Blogging Against Disablism Day. Both are about caregiver abuse. This one is about misusing power in caregiving relationships. In particular, abuse that most people wouldn’t think of as abuse.

A note on vocabulary. Caregivers are called different things in different contexts. Caregivers, aides, personal assistants, attendants, staff, etc. Sometimes they also have more specific titles like LNA for Licensed Nursing Assistant. Regardless of how any of these terms are used outside of the disability world, every single one of them, in the context of disability, refers to someone with incredible amounts of power over disabled people. Not a person the disabled person has incredible power over. And that goes for even if we hire and fire them ourselves.

I get services from two agencies, a developmental disability agency and a physical disability agency. The DD agency calls caregivers staff. People from the physical disability agency can have all kinds of job titles depending on what their specific job is. The ones I see regularly are called LNAs. None of these terms are considered disrespectful by the agencies using them, or by the caregivers themselves. And when I refer to staff or LNAs, I am talking about people with huge power over me, not people subject to my own power. That will become obvious when I use events in my life to illustrate different abuses of that power.

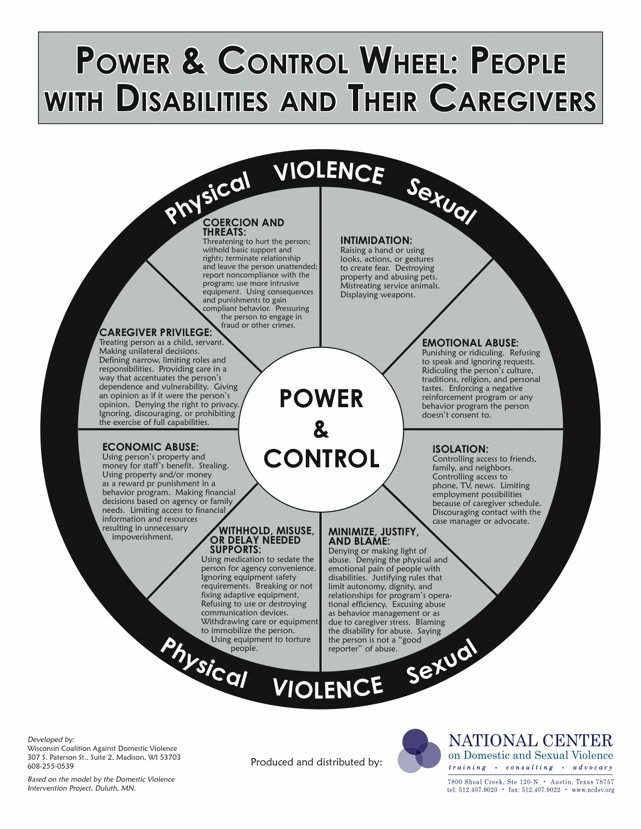

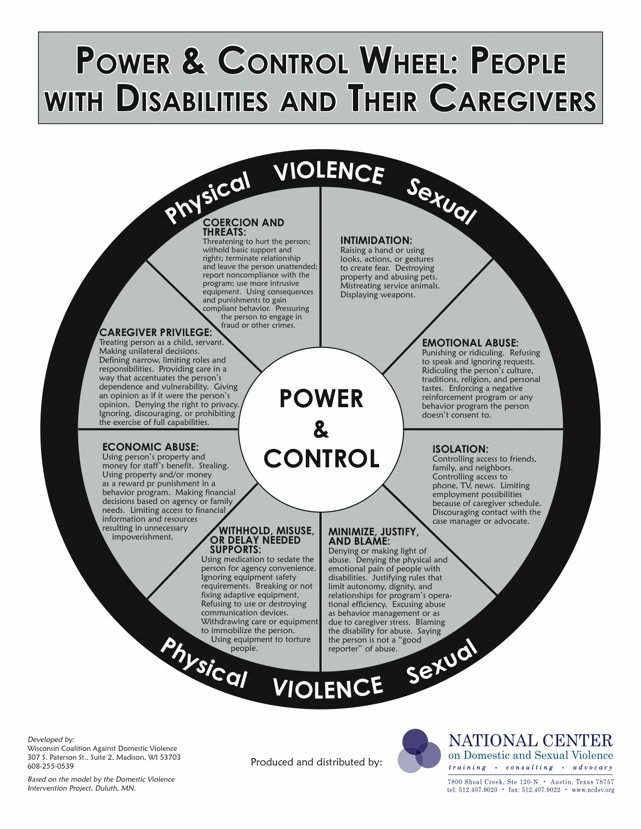

I recently found this graphic developed by the Wisconsin Coalition Against Domestic Violence and distributed by the National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence. It’s called a Power and Control Wheel.

At the top, it’s labeled “POWER AND CONTROL WHEEL: PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES AND THEIR CAREGIVERS”. Around the outer edge, colored black, are listed physical and sexual violence. The middle says “POWER & CONTROL”. In between, in grey, are various forms of abuses of power and control.

Since this is a graphic, and since the PDF file is kind of muddled in terms of the placement of lines that a screen reader might use, I’m going to transcribe what’s on the graphic and then provide examples from my life and the lives of people I know. But first, the graphic and the PDF:

A PDF of this file is available from the National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence here. So on to descriptions of each section of the wheel.

COERCION AND THREATS:

Threatening to hurt the person; withhold basic support and rights; terminate relationship and leave the person unattended; report noncompliance with the program; use more intrusive equipment. Using consequences and punishments to gain compliant behavior. Pressuring

the person to engage in fraud or other crimes.

Threatening to cut off support is a huge one I see all the time. I’ve had people literally walk out the door in the middle of a shift without assisting me with vital things, just because they were angry with me. Or just because of things I can’t even figure out. Like more than once a person has come up behind me and startled me, and I jumped and shrieked involuntarily, and they said “That’s it, I’m out of here” and turned around and walked out the door. That’s basically denying a person disability services on the basis of the person being disabled, but it happens all the time.

Using consequences and punishment to gain compliant behavior is something that pretty much all institutions do, including the kinds of institutions that most people don’t call institutions. My special ed school was huge on that. And the consequences were things like being locked in a dark closet for hours.

I found it amazing that they listed the part about pressuring people to commit fraud. Years ago, I had a staff person who was very manipulative in general. He would do things wrong on purpose and then blame them on other staff, in an attempt to get me to trust him alone and to distrust other staff. I’d experienced that before, so I knew what I was looking at. He also claimed to have been fired from this job in the past because he was “just too political” about disability rights.

But the very last straw was one morning when he came in and explained that he had “connections” at the local hospital. He knew that I was having trouble obtaining a certain medication that Medicaid refused to cover. He claimed that if I was “already in the system”, Medicaid would have covered the medication because they only refused to cover it for people who weren’t taking it already. He told me that he could use his “connections” in the hospital to change my records in the computers so that it looked as if I’d already been taking it, and that then Medicaid would cover it.

The moment he was gone, I contacted my case manager and told him that I was afraid of this guy, and that he’d tried to get me to commit Medicaid fraud. The very last time I saw the guy, he must have seen the writing on the wall. Because he told me he was on the verge of being fired again for “being too political” so he was going to quit before they could fire him.

But one mistake they made was ever allowing him back into my apartment after I’d reported what happened. Caregivers can turn outright violent if they think you’ve reported them for abuse or incompetence. Not all of them do, but given their extreme power over disabled people, it’s dangerous to allow them to be alone with a client once they know they’ve been reported for abuse or that their job may be ending. I’ll get to an example of that later.

The times when people threaten to use more intrusive equipment have usually been when I’m dealing with the medical profession. I once refused to take a pill I was allergic to, and without even stopping to figure out why, a doctor threatened to stick a suppository up my ass. She wouldn’t let up on that and other threats until my power of attorney contacted Patient Relations on my behalf. In the psychiatric system, refusing medication often means being tied down and injected with it. There’s something very punitive about the way these systems handle someone not immediately going along with whatever they want.

I’ve also had people, both medical and otherwise, do things to me in ways that hurt. On purpose. That didn’t have to hurt. I once had a doctor order a blood gas not because I needed one but because he’d decided I was a bad patient. He pretty much said outright that this was why. My problem? Saying that his treatment for asthma wasn’t helping my breathing problem that wasn’t asthma. Because of him, they overlooked an infection that did permanent damage to my lungs. Other times it’s just a matter of providing the same services as usual, only in a violent way. It’s hard to describe the difference. It’s like there are gentle ways and there are violent ways to help someone transfer into a wheelchair.

There’s also the threat of being considered a bad client. The kind who complains too much. The kind who bans too many people from your house. I’ve put up with all kinds of things for the sake of not being considered that kind of client.

That includes sexual abuse. That’s another kind of abuse where sometimes it’s all about the way the person does things. In this case I needed to be bathed in bed and have different lotions appled to various parts of my body. And this woman… I can’t describe the way she did it. It was like a sexual caress. It was all wrong. And yet I put up with it every day because I knew that nobody would believe me, because the abuse was too subtle, because my sexual orientation would be called into it, because I would be told I was misreading social cues, all kinds of reasons. But mostly because I couldn’t afford not to get those services.

One of the worst threats to withhold care was explicit and came from a really bad case manager. Even though prior to coming to this DD agency, I had had one staff person for several years — an eternity in human services — he started spreading rumors that I was always refusing staff before I got there, and switching them all the time.

There were two people that I began refusing to allow into my apartment. One of them had a severe cognitive impairment that prevented him from understanding three-word sentences some of the time, in ways that directly endangered me. I reported this to the agency and he thought I was saying that as an insult. I told them I wasn’t. They told me nobody with a severe cognitive impairment would be allowed to work for them. Years later they figured out he had been hiding his Alzheimer’s from the company in order to avoid getting fired. I never got an apology.

But in the meantime, they didn’t know this. And there was this other guy who was constantly proselytizing to me. Two people out of dozens of potential staff.

Well they started telling me things like “Nobody really wants to work with you, you know.” When staff told me they liked me, this case manager would tell me they didn’t really, and that everyone hated working with me. He kept sending in the two guys I’d said could not come in, and telling me that if I refused them, I would not get services at all. And that he would write me down as unilaterally refusing all services from the agency.

Later he threatened to put me in this agency’s version of institutional care if I didn’t do what he wanted. I filed a complaint about all of this and more, and I won.

Back in California, there was an agency that had a policy of firing staff that clients liked, or pressuring them into quitting. Usually through blackmail, and setting them up to look like they were abusing people. Meanwhile, if any of us reported real abuse, they’d give that person a promotion. It was twisted but very deliberate on the part of two case managers who had the most power and who treated it like a fun game to mess with our lives. I’m not kidding.

One time, even, I reported one staff person for abuse. Later on, a very good staff person, well-liked by the entire company. Was fired for abusing clients. In the same, specific, way, that I’d reported the other person as doing. There was a client who couldn’t write for himself. So he’d dictate an email and they could write whatever they wanted. And so one day they wrote an email, as if from him, accusing the good staff person of abusing him in the same bad way as the person I’d reported. He had no clue what was going on when they fired her.

But anyway. Because of my role in reporting actual abuse. They refused to give me services at all. They blackmailed one good staff person into quitting a day before she was going to be fired. She refused to tell me what they’d done to her, but she was shaking the entire shift. They did this on purpose, because the next day was the day she would train the new staff person about what I needed them to do. This left me with a new, but good, staff person, who had to learn everything from scratch. This amused the case manager.

But then the new, good, staff person, was fired in the scenario I described above. And they just refused to give me services at all for months. This person ended up doing services for me all that time without much if any pay (she got a little from a different state agency) because she couldn’t stand what they were doing to me.

The way they did it, was they’d take careful note of things I couldn’t have in staff — for instance people who couldn’t lift wheelchairs — and then they’d say “We could only find a person who couldn’t actually do anything for you, so you’ll have to accept that or nothing.” It was really weird. At one point they deliberately triggered me into a meltdown, and then smiled at a (good) staff person and said “See what you made her do?” Then blamed her. It was a mess. But it basically all amounted to withholding services because I reported abuse.

CAREGIVER PRIVILEGE:

Treating person as a child, servant. Making unilateral decisions. Defining narrow, limiting roles and responsibilities. Providing care in a way that accentuates the person’s dependence and vulnerability. Giving an opinion as if it were the person’s opinion. Denying the right to privacy. Ignoring, discouraging, or prohibiting the exercise of full capabilities. Raising a hand or using looks, actions, or gestures to create fear. Destroying property and abusing pets. Mistreating service animals. Displaying weapons.

The very first time I saw anyone from the DD agency I get services from, I knew they were going to be trouble. I was in the parking lot before they were going to interview me for services. And what I saw made me nauseated.

A disabled man got out of a car. He banged his leg a little bit. The staff person swooped over to him and said, in exactly the baby-talk voice it sounds like, “Awwwww I kiss your boo-boo all better!”

I knew at that point that if they actually gave a shit about not treating people like children, she wouldn’t be working there, because she was doing it in public in a flagrant way that meant she’d had to have done it in front of people before.

And as an agency, they really don’t give a shit. There’s individual people who give a shit, but a lot who don’t.

The agency that really has problems with privacy, is the physical disability agency who helps me bathe. Yes, they normally see me naked. Yes, they normally clean my private parts in ways I can’t clean them myself. But that does not mean they should be allowed to deny me privacy in other situations. In fact, it means they should be giving me more privacy in other situations.

The big thing is walking in on me in the bathroom. I’ve never had much of a sense of body modesty. But when I learned that puts me at risk of abuse, I’ve been trying to learn it. This is not helped when people walk in and stare at me when I’m taking a shit. There is no excuse for that except in circumstances that don’t apply here. And yet if I complain to the agency about it, they’re puzzled as to why it’s even a problem. If I want to keep them out I pretty much have to lock the door, and then they’ll stand out there loudly complaining about how much time I’m taking.

The rec program from last summer was huge about treating people like children, making unilateral decisions, and all of that kind of stuff. We had to ask permission to do much of anything at all, and… I don’t even have the mental energy to go into everything that happened there. I already described it in another post.

Even otherwise good staff frequently make decisions about stuff without consulting me. Sometimes I agree with them, sometimes I don’t, but people should at least ask.

And providing their opinions as if they were my own? That’s happened to me all the time. It’s made worse by the fact that people will talk to a staff person rather than to me. Then the staff person can answer on my behalf without even asking me what I believe.

ECONOMIC ABUSE:

Using person’s property and money for staff’s benefit. Stealing. Using property and/or money as a reward pr punishment in a behavior program. Making financial decisions based on agency or family needs. Limiting access to financial information and resources resulting in unnecessary impoverishment.

What usually happens with me is more subtle. Which is that people will spend money in ways that really screw up my finances, but nobody holds them accountable.

I have a friend who is very poor. She asked someone to send something by mail or Fed Ex or something, with whatever the normal fare was. They bought the most expensive option, like next day air or something, and brought the expense up to $100. She then didn’t have any money to spend the rest of the month. The person was never held accountable, and my friend didn’t have the cognitive or physical stamina, or money, to fight them in court or something.

I can’t count the number of times I’ve had people do similar things to me. Or they’ll spend over $100 on groceries without telling me. Which is why I now have a ledger system in place where people have to write down how much they spend. But it doesn’t stop people from spending it in the first place.

For someone without very much money, this is a huge deal. And yet there’s very little recourse, either when people spend too much, or when they destroy expensive property.

As far as using my property for their own purposes? I had this staff person years ago, who was always evangelizing to me about his religion. And was always trying to hold me to standards from his religion, when it wasn’t my religion to begin with. But then he began telling me things like “I provide these services for you, so you need to do things for me in return.” What I had to do in return, apparently, was use my printer to print off copies of a pamphlet regarding his religion.

I also at one point had been prescribed Vicodin after surgery. I didn’t use all of it. So a staff person started taking it. As in, taking it and using it. I couldn’t complain because I couldn’t afford to have her not working for me.

WITHHOLD, MISUSE, OR DELAY NEEDED SUPPORTS:

Using medication to sedate the person for agency convenience. Ignoring equipment safety requirements. Breaking or not fixing adaptive equipment. Refusing to use or destroying communication devices. Withdrawing care or equipment to immobilize the person. Using equipment to torture person.

I once lived at a residential facility that made a big deal about the fact that they didn’t use restraints or locks on the doors. What they didn’t tell people was that they used medication and behavior modification to ensure that there were restraints inside people’s heads. The same happens in a lot of systems that claim to be “more humane” than places that use locks and restraints. I’d far rather just be tied down, at least it’s honest.

I remember one staff person who had been great for years, and then something changed. Suddenly she began withdrawing support at random times, that seemed designed to hurt me and make me miserable. She made me sleep on the floor rather than on the only bed in the apartment. She would not allow me to lie down on that bed even when I’d just had a long airplane trip and desperately needed a place to lie down.

When I moved house, she refused to allow me any role in unpacking or deciding where my belongings went. And that was when I first experienced the part where she began messing with my head. She said, in a tone as if I had requested something ludicrous and impossible, “I am not going to sit here and ask you where to put every single thing!” I began to doubt myself so much that I spent years afterwards asking other staff people, “Is it wrong to ask for that when I’m unpacking from a move?” They all say no it’s not wrong, but I’m still afraid to even write this down lest someone tell me how I’m horrible to staff by expecting them to do things they shouldn’t be expected to do.

Then it started being things where I badly needed something. She had set things in front of the door so that only a walking person could get in and out, but you couldn’t get out in a wheelchair. When I asked her to move these things, way too heavy for me to move, she told me “I’m not your slave.” She convinced me that if I contacted my case manager about her not doing her job anymore, the case manager would see how ridiculous I was being to expect her to do things that she’d done for me for years without complaint.

She later told me that when someone is stopping any kind of relationship with her, she treats them like shit to punish them and to convince herself that it’s not going to be any loss to her. But that’s a really shitty excuse for what she did.

I don’t know who did it, but someone eventually reported her to Adult Protective Services. I don’t know what abuse they witnessed, but it was bad enough that a total stranger reported her. She blamed me and a friend, but we didn’t do it. She wouldn’t believe me when I told her we didn’t. I eventually did tell my case manager what was going on, and she was horrified and said I was not in the wrong.

And yet still. I’m afraid to talk about this. Because on some level I still believe that I’m an unreasonable person who asks staff to do things that they shouldn’t be required to do. Even though since then I’ve asked tons of people and they all said she was in the wrong.

Elsewhere I describe what happens when people outright ignore that I’m typing anything. But another thing happens sometimes. Where they’ll just say to me, “I don’t have time for this” whenever I try to say something. Or they’ll talk over me too loudly for them to hear me, since communication devices don’t usually go up to very loud volumes. There’s this idea that communication ought to be a privilege, not a right, and that I’m only allowed to communicate at times when it’s convenient to others. Or that I don’t get to communicate at all if they’re angry at me for some reason. This becomes even more of an issue at times that I need physical help using a communication device. People seem to think of communication in general as something that’s nice if there’s time but otherwise forget it. It’s all about whether it’s convenient to them, even though times when it’s inconvenient to them are often the times I most desperately need to say things.

MINIMIZE, JUSTIFY, AND BLAME:

Denying or making light of abuse. Denying the physical and emotional pain of people with disabilities. Justifying rules that limit autonomy, dignity, and relationships for program’s operational efficiency. Excusing abuse as behavior management or as due to caregiver stress. Blaming the disability for abuse. Saying the person is not a “good reporter” of abuse.

Caregiver stress is the one that stands out to me here. People have used it to justify literally everything up to serial killing of disabled people. (No, I’m not exaggerating. I wish I was.) And the public buys it. They buy that it is just so stressful to work with disabled people, that abuse is bound to happen. They even say this about murder, even multiple murders, even when the murderers outright admit they only did it for fun.

I’ve done a lot of research into the murders of disabled people, and autistic people in particular. You hear things all the time like “She shouldn’t be sentenced to prison. She already served 15 years of being the parent of an autistic child.” Again, I wish I was kidding.

And if people will use this to justify murders and serial killings, they will use it to justify any abusive thing that happens to a disabled person ever. And they do. All the time. This is one of many reasons that I don’t trust most campaigns for awareness of caregiver stress and burnout. I’m not denying that those things are real. But they’ve become so ingrained in public consciousness, that the instant a crime against a disabled person makes the news, all you hear is “It’s so hard to take care of That Kind Of Person, you really can’t blame them.” Coupled with a lack of focusing ever on the fact that disabled people get burned out from having to put up with caregivers all the time whether we feel like it or not, the usual ways people discuss these things start seeming one-sided and scary.

How bad is it? I know several people who have contacted rape crisis hotlines to report rape by caregivers, and been told outright “You have to understand the kind of stress they’re under, it’s very hard to care for someone like you. They really have your best interests at heart and you should learn to accept that.”

I have told people about things I went through growing up that nobody should have to go through ever. And been told that “being a caregiver is hard, you have to understand that”. As the very first response when I try to disclose horrific forms of abuse. There is no escaping this excuse. And it’s a terrible excuse but people buy it because the disabled person’s side of the caregiver relationship is not taken seriously at all. Even though we’re truly the ones on the wrong end of that power relationship.

Mind you, I know caregiver burnout happens. But any discussion of caregiver burnout has to draw lines about what it’s used to justify. I’ll buy that people will get irritable and snippy. I won’t buy that truly abusing and killing people is ever an acceptable response. Any discussion of caregiver burnout also has to acknowledge the other end, the end nobody talks about. Which is that disabled people get burned out on our caregivers. But that we have no choice but to accept care every day. We can’t take a break without danger to ourselves.

Some places have respite services for caregivers. There are no respite services for disabled people. Ultimately, even if it would make them feel terribly guilty, caregivers can walk away and abandon us without dying. Disabled people cannot abandon our caregivers without dying. That shows one huge power discrepancy in the relationship.

As for all the other things, they are pretty much standard practice in most agencies and institutions. Everything is set up for the convenience of staff and other workers, not for the convenience of disabled people. It’s rare to find a place where this is otherwise. And that means that if abuse happens, it will either be justified as part of the program, or someone will make up ways to make disabled people sound like we’re unreliable reporters.

There was a woman who was a client of the same agency I am a client of. And her caregiver literally would not allow her into certain areas of the house. She insisted that her client could not be home during certain hours. One day, she had a serious bathroom accident at work. Her caregiver refused to allow her to come home. This was reported to Adult Protective Services by her job coach.

The entire investigation basically involved the agencies finding “evidence” that this client was a habitual liar. APS decided that abuse didn’t happen and that the client was lying about it. You hear the same things when it’s sexual abuse. Dave Hingsburger said he went to a rape trial where the agency brought out all the different reasons this person could not be trusted. She tried to say “But I only lie about little things, not about something like this.” As I remember it, nobody believed her. But even when someone isn’t a liar, you can bet that once they report abuse by a staff person the agency happens to like, they will be made into one.

ISOLATION:

Controlling access to friends, family, and neighbors. Controlling access to

phone, TV, news. Limiting employment possibilities because of caregiver schedule. Discouraging contact with the case manager or advocate.

Limiting employment possibilities because of caregiver schedule is the norm for one agency I get services from. They’re the people who provide personal care, which includes things that I absolutely can’t go without.

I don’t have a job and will probably never have a job. But there are two hours a week I ask them not to come, and one day a week where I ask them to come before noon. That’s it. Two are essential meetings with my case manager. One is a day when, if I’m feeling up to it (which is practically never these days), I go to an art program.

I have been told, explicitly, and continually, that even just those two hours a week alone. Without the day when people can’t come past noon. That just those two hours are limiting them too much. That it’s not fair to the LNAs or their scheduler. That essentially if I am not available 24/7, then I have no reason to expect proper care.

They’re the only game in town for the kinds of services they provide, and they know it. So they are able, as an entire agency, to regulate disabled people’s lives so much that if we have jobs, or even a couple meetings a week, we can’t expect care.

As far as isolation goes, the recreational program I was in last summer did that in spades. I was not allowed to use the phone except when they wanted it. When I was extremely ill, like on the verge of needing to be hospitalized, I was not allowed to call my power of attorney for healthcare. And when I tell advocates that we were not allowed to use the phone whenever we wanted, that is enough to send off huge alarm bells. They also only allowed contact with my case manager if they were the ones doing the talking and I was merely in the room. If they didn’t approve of something I wanted to say to my case manager, they refused to tell her what I was typing.

I’ve also experienced a really peculiar form of isolation that isn’t listed here. It’s happened to me several times in several forms with abusive caregivers.

It’s where they try to prevent contact with people, but they don’t do it overtly. They just start dropping tiny little hints here and there, that friends and other staff are not trustworthy people. That they, in fact, are the only trustworthy person in your life. That other people are saying bad things about you behind your back. That nobody else actually likes or respects you. This can be done so subtly that you barely even notice until you realize months later that this is the only person you’re talking to anymore, and they’re being horrible to you.

Related is something I never see discussed anywhere either. Where someone who is incompetent or abusive in almost all other areas, will have one thing they do to make themselves indispensible. It may be working longer hours than they’re technically supposed to, at a time when you’re not getting enough staff hours to meet your needs. It may be cooking you the best food at the cheapest prices that you can possibly imagine. It really accomplishes two things. First, you won’t want to fire them because you’ll lose the above-and-beyond support they’re giving you.

But the other thing is more directly related to isolation. They do all these extra things for you, but they also start doing things to make other staff look bad. It can be deliberately screwing things up for you and then claiming another staff person did it. It can be simply lying outright about someone else’s ability to help you. It can be implying that nobody else would ever do these extra things for you. The result is to elevate themselves while putting all other staff down, and making it so you don’t want to communicate with other staff because you don’t trust them as much as you trust this person.

EMOTIONAL ABUSE:

Punishing or ridiculing. Refusing to speak and ignoring requests. Ridiculing the person’s culture, traditions, religion, and personal tastes. Enforcing a negative reinforcement program or any behavior program the person doesn’t consent to.

I would add to this one something that specifically happens to people who can’t speak and use other means of communication. I have communication devices that speak, but a lot of time I have used ones that don’t speak to save time and energy. This means that someone had to read the screen. Sometimes when staff have been angry at me, they simply refuse to read the screen. That’s a level above and beyond the ordinary silent treatment because it makes it impossible to say a word to them even when it’s important.

INTIMIDATION:

Raising a hand or using looks, actions, or gestures to create fear. Destroying property and abusing pets. Mistreating service animals. Displaying weapons.

The last time I had a staff person raise a hand to me, it wasn’t even my staff person. This is the story I promised earlier about what can happen once you start challenging a caregiver’s power, or once they know they’ve been fired.

In this case, the person was a friend’s staff person. She was really good, except for one thing. She could not stay out of my friend’s stuff. If you asked her not to, she’d either pretend not to hear you, or laugh like you just made a huge joke and do it anyway. In fact, even if she wasn’t already doing it, the moment you asked her not to do something, she’d immediately do it. And it was getting to be a huge problem, because she was arranging my friend’s stuff in ways that made it inaccessible from a wheelchair and impossible for my friend to get any work done.

Every time my friend got out important paperwork, for instance, this staff person would “put it away” without asking, even to the point of putting it at the bottom of a box stacked behind and under boxes that my friend was unable to lift. My friend asked me to come along to help her advocate for herself when she finally drew the line for this person. She wanted to simply not allow this person into her living room.

At first, she laughed and tried to go in anyway. When we made it clear we really meant business, though, she began screaming at us. And I really mean shouting at the top of her lungs. She said that she was going to leave and refuse to cook dinner for my friend, who is unable to cook for herself.

I told her that was a form of caregiver abuse and not acceptable. She kept screaming about how she was “NOT THAT KIND OF PERSON” and that I needed to leave, now, and that she was not going to listen to a single word I said. In practice this meant shouting over the top of my communication device, which can only go to a certain volume. I of course didn’t leave, because leaving my friend alone with a staff person who was that angry would have been a serious danger to my friend.

But neither of us were prepared for what happened next. She actually raised her hand to me and took a swing, stopping short only when her hand was two inches from my face. Then she held it there shaking. After we got her to leave, she hung out outside my friend’s apartment for several hours. She claimed that she was out there doing work for another client, but she didn’t have another client during those hours.

Yes, all of this was reported. No, nothing happened to this staff person. That’s what happens in the system, especially in the kind of agency (most of them) that protect staff and not clients. Even in things like murder investigations this is usually true.

She also seriously distorted what we actually told her, when recounting it to other people in the agency. The things that made her the angriest were when we told her that withholding food is considered a form of caregiver abuse, and that the things she was doing with my friend’s stuff involved a power relationship that she wasn’t acknowledging. We carefully explained why it is that people who have this kind of power, often don’t realize it. We went out of our way to explain why she might not have noticed this and that we knew it wasn’t her fault. When she repeated it to others, it was “They told me that I was an evil, power-hungry person who abuses disabled people for fun.”

This is also an excellent example of why a staff person should never be left alone with someone who has reported abuse, has let them know they won’t be working there any longer, or that kind of thing. This woman gave no warning at all that she was going to turn loud and violent at a mere request to stay out of a specific room. I tell staff to stay out of a particular room sometimes for all kinds of reasons, and have never gotten a response that intense.

So basically…

There are tons of different ways to abuse power, and this only covers some of them. But this is the best description I’ve ever seen of stuff that nobody ever even acknowledges as a problem. Hitting people and sexually assaulting them are not the only kinds of abuse out there, and in some circumstances they’re not even the worst.

Also understand — I’m not saying that all caregivers are abusive, or even that all caregivers who do a few of these things sometimes are “bad staff” overall. But it’s hard to have power and not abuse it. And people need to be aware that caregivers have this unacknowledged power. And that lots of them abuse it. And that very few people care. Getting services is not a walk in the park. You will inevitably encounter people doing all these things and more. And you have to be prepared.

Contrary to what most people believe, caregivers are not selfless, self-sacrificing saints who never do us any harm, yet shoulder a great burden that leads to burnout, which excuses anything they might do wrong. That’s not even true of the best ones. Caregivers are human beings. Human beings do a lot of bad things to each other. Especially people they have power over. Caregivers have that power. And it is not wrong to talk about it, to point it out, and to say that what some of them do is very wrong and destructive, and not excused by burnout or stress.

And I’m not talking without experience here. I’ve provided care for other people. And despite the inevitable stresses, you have to find ways of handling them other than punishing the person you’re supposed to be assisting. You also have to be constantly aware of your own power.

I’ve also had caregivers who, while very good in some areas, did some of these things. And I’ve had to make decisions about that tradeoff. Should I find someone who does things worse overall, but who does fewer of these things? Or should I stay with this person and try to work out ways to manage the things they are doing wrong? That’s a decision a person can only make for themselves, and doing some of these things doesn’t automatically make someone the worst choice in caregivers. It all depends on the circumstances and the people. But it’s good to know these things are wrong, even when you can’t seem to avoid them.

Not everyone even knows these things are wrong to do. So I have a printout of this chart posted in my kitchen, and have given one to my case manager for training purposes.

And here are the contact information for the two places that came up with and publish this stuff:

Developed by: Wisconsin Coalition Against Domestic Violence. 307 S. Peterson St., Suite 2, Madison, WI 53703. 608-235-0539. Based on the model by the Domestic Violence Intervention Project, Duluth, MN. National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence. 7800 Shoal Creek, Ste 120-N, Austin, Texas 78757. tel: 512-407-9020. fax: 512-407-9022. www.ncdsv.org.